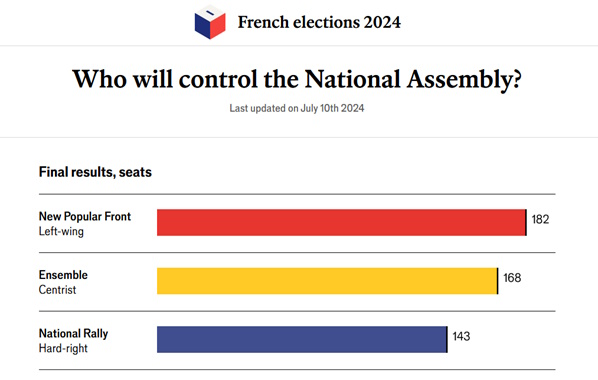

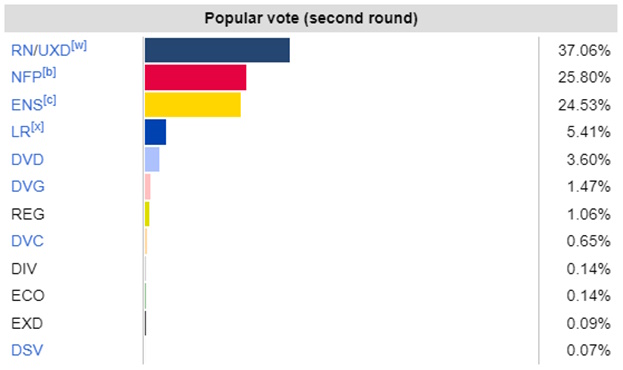

The elections tend to hide the data on the number of votes achieved by the fascist Rassemblement National [RN] party, which emerges as the leading party in the country. In second place is the so-called “Nouvelle Front Populaire” [NFP] with France Insumise [FI]. Macron’s formation comes in third place.

The current French electoral system has encouraged an outcome that, in terms of amount of votes, does not reflect the real relationships between the main political forces of power. With the result that, by number of deputies, NFP prevails over FI and RN, while RN ranks only third. The distribution of deputies shows multiple possible scenarios for the formation of the new government, none of which seems to guarantee sufficient political stability, however. The hypothesis that is considered most likely, taking into account that NFP is a heterogeneous coalition in which the ultrareactionary Socialist Party has slightly fewer deputies than FI, is that of disintegration of this false-left circus, resulting in the emergence of a wing that would go on to ally with Macron. But even in the event that the party referring to the “left-wing populism” of Melenchon and FI were to place itself in opposition, this opposition would be characterized by the revival of “sovereignist” and pro-imperialist themes, within the framework of a populist and social-fascist type of contestation against the far-right, and thus certainly not for a truly popular and anti-fascist opposition.

In that case, the ruling political forces would tend to retrace old paths that helped bring about the current political crisis. However, the situation is even more problematic than before because of the further advance of openly fascist forces.

The French imperialist bourgeoisie is forced to impose government choices that will in any case shatter and delegitimize in the eyes of the masses the NFP and will be increasingly inclined to support a grouping of forces including RN. An eventuality which would break up the liberal-fascist and possibly social-fascist components (in the case of the involvement of pieces of the current NFP) and which would lead, more or less quickly and more or less directly, to the full establishment of the more openly reactionary forces working for the formation and crystallization of a fascist regime.

Some sincere communists and many social democrats, revisionists, Trotskyites, Bordighists, (autonomous) Workerists [operaisti], anarcho-syndicalists, etc., believe that in France today (and similarly in the various European countries) there is a bourgeois democracy characterised by a kind of conservative liberalism, more or less marked by an authoritarian concentration of power of the government executives. Consequently, they deny that France, like the other imperialist countries of the US-led western bloc, is characterised by advanced processes of corporatisation and fascisation, in respect of which the advance of extreme right-wing forces can only be a significant accentuating and accelerating factor. These positions are politically dangerous.

On the one hand, in fact, these are characterized by bourgeois-democratic illusions about the possibility of organizing the mobilization and struggle of the masses while benefiting from effective democratic and trade union rights and freedoms. The consequence is that there is a tendency in the development of political activity toward the promotion of opinion and trade union movements. In some cases is consequently theorized that the masses tend to spontaneously develop forms of mass organization and movements of struggle, economic and political in character, antagonistic to capitalism, and that radical political and social change can only be the expression of the unification and growth of these movements. For some of these radical left and far left tendencies, often hegemonic in different European countries, the form of revolution will have to be that of radicalization of movements and mass organizations. Thus it is argued that the party is an expression and synthesis of the dialectic between the formation of communist cadres and the development of the initiative of alternative unions and mass struggles.

On the other hand, the thesis that claims that “bourgeois democracy” would exist in European countries is not only a cornerstone of reformist and movementist politics and strategy, but also leads to the undervaluation of fascism. In some cases, this undervaluation, as in various populist leftist and Trotskyist positions, becomes outright collusion. Theories of fascism as bonapartism, that is, as an expression of the crisis of the middle classes that would express both reactionary and revolutionary tendencies, ground this indirect collusion with fascism. Moreover, the very political line of the formation of the NFP is a socialfascist combination of reformist demagogy, socialist phraseology, nationalism, defense of the reactionary state and promotion of French imperialism.

We must fight against these reactionary positions that sell the various imperialist states as bourgeois-democratic. From a philosophical point of view, one cannot start from an idealistic conception of “bourgeois democracy” which is first summarized in abstract political formulas and which, later, would be substantiated in a specific order and system of representation of a specific country. Politics is only the concentrated expression of the economy. Thus, to approach the question from a Marxist point of view, one must start from the problem of the transformation of capitalism into imperialism and the question of the formation of “state-monopoly capital.” Bourgeois democracy was the product of the contradiction of the liberal bourgeoisie against the feudal aristocracy and was the expression of a capitalism based on free competition. This resulted in a certain distinction between ‘political society’ (the repressive bureaucratic machine) and ‘civil society’ (the set of bourgeois parties, associations, and institutions deputed to the exercise of bourgeois hegemony over the popular and proletarian masses). With the development of imperialism and the merging of the monopolies with the State, the liberal bourgeoisie becomes organically counter-revolutionary. This class constitutes itself as an economic and political oligarchy that directly takes over the direction of the state, accentuating its repressive features and developing a corporatist hegemonic system at its service, i.e. a ‘civil society’ closely linked to its interests, charged with representing its basic economic and political needs.

With the development of State Monopoly Capitalism after World War I and the crisis of the late 1920s, capitalism enters the phase of general crisis. On this basis, imperialist countries become, albeit in different forms, corporatized. Bourgeois democracy is emptied of all democratic content and is transformed into a form of open fascism or masked by a liberal veneer. With the end of World War II, both in France and in Italy and Federal Germany, much of the fascist regime was reintroduced within the State. So a fortiori we could no longer speak of “bourgeois democracy.”

To take one topical example among many others, it is therefore quite wrong, as well as patently false from a historical point of view, to consider parliamentary forms based on presidentialism, majoritarian systems, the role of technicians and experts, etc., as simply liberal forms and not instead liberal-fascist or properly fascist.

The theories of the past decades on neo-liberalism and globalization have covered and concealed all this, providing the ideological basis for postmodernism, leftist populism, and movementism.

The fact from which to start, however, is not so much that of the various possible scenarios, but that of the strategic objectives pursued by the large French finance capital representative of a strong imperialist country, albeit unable to compete on an equal footing with Germany and still largely subordinate, within the array of Western imperialist countries, to the U.S. superpower.

The French big bourgeoisie finds itself moving within the framework of the general crisis of capitalism and its terminal nature characterized by a growing contradiction with the oppressed peoples, which is reflected within French territory itself, and by a World War III, which presents itself as a long and protracted war of position, in fact already begun with the inter-imperialist war in Ukraine. The French big bourgeoisie is thus today compelled to accentuate its imperialist expansionism and its warlike interventionism, to try to wage “war” between the various components of the French popular masses, to work to impose increasingly openly dictatorial government executives, to accentuate the economic and political offensive against the proletariat and the most exploited strata of the petty bourgeoisie, to tear down the most basic rights and to increase repression. All this means increasing impoverishment of the popular masses, corporatism, nationalism, racism, war and fascism. It is up to the hegemonic system built by the French bourgeoisie to find the best way for the imperialist bourgeoisie to form stable and efficient governments capable of interpreting and representing these strategic directions while gathering as much support as possible among the broad popular and proletarian masses. This was the purpose of the last elections in France. Both RN, FI and NFP took the field competing with each other to find a solution to these problems and contradictions. The outcome of the elections shows that today the situation has worsened. No coalition, in fact, is able to guarantee effective political stability. Moreover, any governing coalition will only accentuate the disconnection of the broad masses of the proletariat and the popular strata from parliament. The consequence is that this disconnection can easily translate into a shift of substantial sectors of the masses to the far right.

Although there is an important party core in France based on Marxism-Leninism-Maoism, which was the promoter in the last elections of a significant campaign of electoral boycotts working for the formation of a revolutionary bloc, a revolutionary mobilization of significant sectors of the proletariat and the popular masses has not yet developed, which remain largely under the hegemony of the bourgeois forces.

The French popular masses will take the field and fight against the far right. If they supported the NFP they did so with this intention, albeit in an illusory way. There is no different way out on the horizon in the development of the struggle against fascism and imperialism than that of building an anti-fascist bloc with proletarian hegemony for the opening of a revolutionary process. This requires the struggle not only against the extreme right, but also against a social-fascist, populist, Trotskyist left, etc., which hinders the development of class consciousness, organization and mobilization. Only the development of the French Marxist-Leninist-Maoist Communist Party can ensure all this for the proletariat and the popular masses.

NEW HEGEMONY