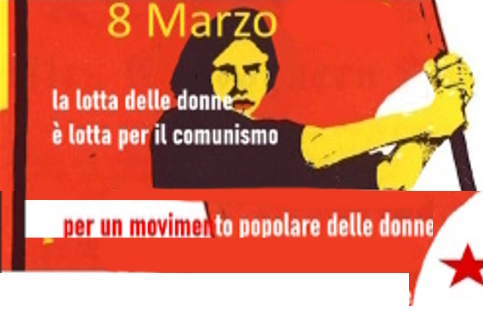

March 8 raises the general question of the struggle for women’s liberation. The revolutionary ideology of the proletariat, starting from its foundation with Marx and Engels and reaching in the later stages to Marxism-Leninism-Maoism, gives a historical-materialist explanation of the underlying reasons for this expression and indicates precisely why the fate of women is linked to communism and the struggle for its affirmation. Women lost their prestige and freedom with the collapse of primitive communism and the advent of class-divided societies based on the oppression and exploitation of a minority against the majority. From slavery to feudalism to capitalism and imperialism, women have continued to be relegated to a condition of marginality and subalternity. All the most progressive steps in the development of humankind up to the proletarian revolution with its historic achievements have foregrounded women’s prominence and fueled the struggle against their oppressed condition. The revolutionary ideology of the proletariat, Marxism-Leninism-Maoism, is the only theoretical explanation that can illuminate the history of women and is the only worldview that shows the way to their ultimate emancipation.

The feminism that began to flourish in Europe in the first half of the nineteenth century as a manifestation of liberal bourgeois tendencies and revolutionary bourgeois-democratic tendencies had unquestionably a progressive background. After this period, with the emergence of Marxism, as the theory of the proletariat that was becoming established on the world stage through revolutionary struggles advanced, the bourgeoisie now in power turned from a revolutionary class into a counter-revolutionary class. All of this implied that by the end of the nineteenth century, as capitalism entered its terminal phase, that of imperialism, the feminist movement was substantially reduced to the women of the liberal bourgeoisie and, while still retaining certain progressive traits, as a whole was evolving in a reactionary direction. In contrast, the most advanced women and men of the working class and popular masses, under the guidance of Marxism were developing their consciousness as a class, identifying in the interests of the bourgeoisie interests antagonistic to those of the proletariat.

Thanks to the establishment and expansion of Marxism first and Marxism-Leninism and Marxism-Leninism-Maoism later among the proletariat and the popular masses in most parts of the world, the twentieth century saw revolutionary communist parties flourishing at various times in almost every country. Within these parties women and men participated side by side in the struggle for the advancement of Socialist Revolution in imperialist countries and for the establishment of New Democracy Revolutions in countries with bureaucratic capitalism. This was done in the full knowledge that there can be no real emancipation of humanity, real equality between men and women and real elimination of women’s oppression in a class-divided society. Just as it has always been clear to these revolutionary parties, women and men that the real emancipation of women is inextricably linked to the struggle for the abolition of private ownership of the means of production and the exploitation of a handful of men over the majority of humanity. The victorious experiences of the revolutions in the USSR and China, including the experience of the GRCP, were the only experiences that achieved actual large-scale revolutionary changes in the political, socio-economic and cultural condition of women and set an example for all revolutionary and sincerely democratic women worldwide.

In Italy, the struggle for the emancipation of revolutionary women reached its zenith in active participation in the anti-fascist civil war and Resistance for the establishment of a People’s Democracy on the road to Socialism betrayed and liquidated by the Communist Party headed by Palmiro Togliatti. Among other things, Togliatti worked against the emancipation of women, launching a vast ideological campaign aimed primarily at erasing the leading role of women communists during the Resistance. In this regard, as early as April 1945 he engaged in various ways in issuing directives to the party to hinder the participation of partisan women in the processions that paraded inside liberated cities in celebration of the victory over Nazi-Fascism. The campaign continued with the explicit intent of relegating them to the private sphere, which relegated them to the role of family care and assistance within the home. Togliatti’s CP thus reconfirmed and sanctioned continuity, even on this level, with the obscurantist ideology of the fascist regime and the church.

In the Italy of the mid-1960s, the feminist movement reappeared briefly and then quickly merged into the various groups and organizations of the then extreme left. Between the 1960s and 1970s and in the years immediately following, going against the male chauvinism and the mystifying interclass ethos of “we are all comrades” that always characterized organizations such as the so-called “Marxist-Leninists” the “Trotskyists and Bordighists, AO-DP, Lotta Continua and part of the Autonomia Operaia areas, the banner of the struggle against women’s oppression and of the indissoluble link between women’s liberation and the struggle for communism was being wielded mainly by the combatant organizations. The prominence of communist women was in fact a characteristic feature of these organizations, particularly the main one among them. The movementist character of these organizations and their eclectic positions played a decisive role in the onset of their crisis and subsequent defeat.

While all this was taking place, the groups and movements hegemonized by the areas of opportunist and petty-bourgeois revolutionarism of critical Marxism and the new left were already evidencing by the mid-1970s those dynamics that would result in profound ideological and political regression. The external pressure represented by repression and liberticidal laws only mattered because it could operate on the internal causes of the groups by amplifying them. The center of the issue lay in the theories, strategies and ideological and political lines of these forces. Thus a potentially revolutionary process, characterized by a relevant investment of individual energies and lives, ended up being transformed, in line with the interests and expectations of the class adversary, into an operation, albeit partial and momentary, of reorganization and reconstruction of reactionary civil society also through the selection and co-optation by the petty-bourgeois political class of a relevant part of these organizations.

The explosion of the dynamics of the opportunist group crisis also expressed itself in the form of the re-emergence of feminism.

While previously predominant in all opportunist groups was male chauvinism and, in a mystifying and idealistic manner, the identity myth of a “communitarian” ethic conceived as the immediate possibility of new, no longer oppressive, proprietary and competitive relations between men and women capable of connecting the personal and private sphere with that of political militancy, all this was shattered as the political and ideological crisis of such groups erupted. The path of feminism, however, was limited to replacing the idealistic communitarian identity ethic with another equally idealistic and ultimately regressive myth, that of the structural character of the antagonism between men and women within the party, the class of the proletariat and the popular masses. Whether the genesis of this “structural character” was then attributed from time to time to gender difference or the role of capitalism is secondary.

The revival and rise of the feminist movement represented an attempt to respond to the ideological crisis of political organizations that had emerged with particular rawness on the level of male-female relations and, simultaneously, a further step in the decomposition of opportunist groups. This political and ideological crisis contained within itself a great evolutionary potential for an overall critique of the hegemonic positions in the movements and constructive dissolution of the petty-bourgeois revolutionary groups of the 1970s, with related opening of a different perspective of organization and struggle for women’s liberation linked to the perspective of communism. But the answer was to fix and enshrine on the ideological, philosophical and ethical level the antagonism between men and women within the same proletariat and popular masses.

This culturalistic and idealistic problem will continue to reproduce itself in the following years in new forms. The crisis of “communist,” “Marxist-Leninist,” movementist and anarcho-bureaucratic groups and areas will always continue to re-propose and represent this dual possibility, as far as the women’s question is concerned: either feminism (more or less eclectically and confusingly “Marxist”) or women’s struggle for communism. This is with good grace to those who will continue to racialize within it all, trying to put one and the other together.

Thus starting from the thesis of an original difference between men and women, which would be a priori expressed in a structurally antagonistic relationship, feminist thought has promoted corporate practices of struggle for “identity interests” or limited to a sterile culturalism of ‘re-signification’ of language. Passing off identity interests as objective reality, feminism, in all its variants, intentionally or unintentionally has worked to dig an antagonistic ditch within the popular masses. This has also worked with regard to various forms of alleged “Marxist feminism,” which conceive of the man-woman contradiction not as an articulation of the class contradiction but as a specific contradiction supplementary to the class contradiction.

The currents of feminism in the 1970s and those of today are linked to the idealistic-subjective philosophy of postmodernism operating in the service of imperialism. Objectively, by denying in general the class character of society and the class struggle as the law of historical and social development and, in particular, that the “man-woman contradiction” can only be an articulation of the class contradiction reflected within the people, the various currents of feminism have played and play their role in supporting a process of passive revolution (Gramsci).

In line with the theories of postmodernism, feminists have advocated and support special and subjective interests, emphasize and defend so-called “gender” or “identity” politics, create illusions among the popular masses, attributing to the abstract claims of “recognition of difference” or “deconstruction” of “ male language” the power to trigger social change based on empowerment. . This, on the contrary, amounts to reproducing an antagonistic contradiction between men and women belonging to the popular masses, to fragmenting them by subordinating the collective social interests of the proletariat to “identity interests.”

Even the currents of “Marxist” or “anti-capitalist” feminism, which do acrobatics to keep the reference to Marxism in their theoretical framework, are in fact in line with the theories of postmodernism and reject Marxism’s own philosophy, historical-dialectical materialism. The theorization by these currents of separatism in communist organization and the theory of the double revolution leads to a denial of the fact that the only criterion that can be foregrounded is that relating to class contradiction. The contradiction between men and women in the proletariat and the popular masses is, in respect to its structural dimension, of a non-antagonistic type, a contradiction therefore within the people. Without the assumption of the centrality of the class contradiction, it is inevitable to come to deny that the struggle for women’s liberation is an internal and constitutive part of the communist perspective, and thus it is inevitable to reject the philosophy of materialism-dialecticalism, a theoretical synthesis of knowledge and practice relating to the entire history of humanity, class struggle and the ICM.

In this sense, the title of Carla Lonzi’s 1970 pamphlet “Let’s Spit on Hegel,” with its disdain for materialistic dialectics and the proletariat’s worldview, can be considered the synthesis of the “philosophical program” of all feminism in the second half of the 1970s and the following decades up to the present.

Without historical-dialectical materialism, it is impossible to analyze and understand the condition of women’s oppression of the working-class masses, it is impossible to point the way to the ultimate liberation of women, it is impossible to transform society. That is why it is necessary to work on the establishment of a communist party and the construction of a consistent perspective and line that, in the struggle against the oppression of women, against the dominant male chauvinism and bureaucratism in the organizations of the far left, against the sectarian and individualistic logics of postmodern feminism*, will make it possible to work to restore meaning and momentum to the leading role of women of the proletarian and popular masses and to arrive at the formation of an effective popular movement of revolutionary women**.

NUOVA EGEMONIA

*On the issue see the useful and well-set pamphlet by the POPULAR FEMININE MOVEMENT OF BRAZIL<<“Postmodernism” and feminism: individualism and bourgeois relativism in the service of imperialism>> https://nuovaegemonia.com/2023/08/23/postmodernismo-e-femminismoindividualismo-e-relativismo-borghese-al-servizio-dellimperialismo/ >>

**The text of this article highlighting the link between the struggle for women’s liberation and the struggle for communism picks up on a number of themes extensively covered in the book edited by Nuova Egemonia ‘COMMUNISM, THE WOMEN’S LIBERATION FIGHT AND THE CRITICISM OF WOMEN’S FEMINISM’ . The book can be downloaded in full at the following link https://nuovaegemonia.com/2024/12/07/un-libro-maoista-per-la-lotta-di-liberazione-delle-donne/